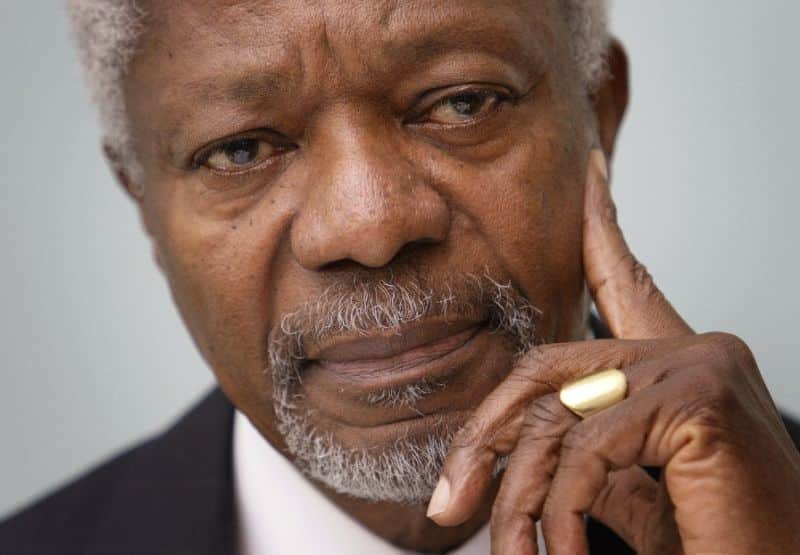

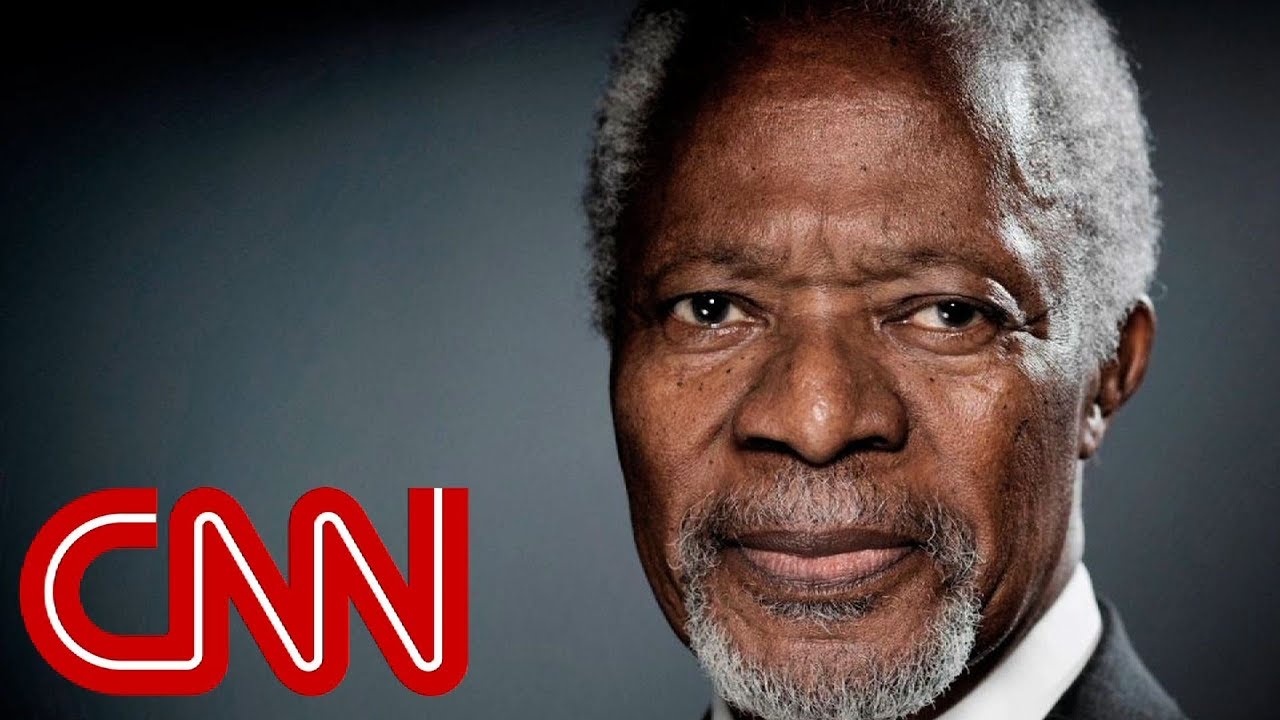

United Nations Former secretary-general Kofi Annan died today Saturday, August 18, 2018, at the age of 80. He received the Nobel Peace Prize laureate jointly with the United Nations (UN) for their for a better organized and more peaceful world.,

The Ghanaian diplomat passed away at a hospital in the Swiss capital, Bern, on Saturday after a “short illness,” his foundation said in a statement.

“Kofi Annan was a global statesman and a deeply committed internationalist who fought throughout his life for a fairer and more peaceful world,” the statement said.

“He was an ardent champion of peace, sustainable development, human rights and the rule of law,” it added.

Annan served as the seventh UN chief for almost a decade, from 1997 to 2006. Having joined in 1962, he was the first staffer to take over the top UN job and the first to hail from sub-Sahara Africa.

In 2001, he received the Nobel Peace Prize jointly with the UN, lauded for “bringing new life to the organization.”

On Saturday, current UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres described Annan as “a guiding force for good.”

“In many ways, Kofi Annan was the United Nations. He rose through the ranks to lead the organization into the new millennium with matchless dignity and determination,” Guterres said in a statement.

Mixed legacy

Born in Kumasi, Ghana’s second most populous city, on April 8, 1938, Annan spent the first 18 years of his life under British colonial rule.

But on March 6, 1957, Ghana became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to break the chains of colonialism, a momentous event he would later describe as “very powerful.”

“I grew up with a sense that fundamental change was possible … I saw that things could change, and I had a sense that I could help change things because I had seen it happen at such an early age,” Annan said in a 2013 interview.

At age 26, he joined the UN and rose up to be the global body’s head of peacekeeping operations.

He held that role in 1994 when more than 800,000 Rwandan civilians – mainly from the minority Tutsi population but also moderate members of the Hutu majority – were killed by ethnic Hutu during a campaign of mass murder that occurred over the course of some 100 days between April and July.

In July 1995, while Annan was serving as the special envoy to the former Yugoslavia, Bosnian Serb armed forces killed more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in 10 days within a so-called UN “safe area” in the town of Srebrenica.

The massacre which occurred in these countries marked the worst mass killing on European soil since the end of World War II five decades before.

In both cases, Annan came under fire for his perceived failure to do more to prevent the atrocities.

He would later admit to having “failed” on Rwanda, suggesting he “could and should have done more to sound the alarm” despite having pressed UN member states to offer more military support for the UN peacekeeping mission in the country.

“This painful memory, along with that of Bosnia and Herzegovina, has influenced much of my thinking, and many of my actions, as secretary-general,” Annan said in 2004.

Annan’s achievements at the UN, however, were many.

From working to tackle the AIDS epidemic to heading the push for the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals, which set targets for eradicating poverty and improving well-being globally, his efforts won gains for millions of people around the world.

He also drove reform within the organization of the UN itself, notably reorienting the UN’s focus towards human rights issues, embodied by the creation of the Human Rights Council in 2006.

After stepping down from UN’s helm, Annan in 2012 served for six months as its special envoy for war-torn Syria before resigning in protest over a lack of unity by world powers and growing militarisation on the ground which, he said, made the role “mission impossible.”

More recently, Annan chaired an independent commission investigation into Myanmar’s Rohingya crisis, which saw more than 700,000 people last year fleeing the country to neighboring Bangladesh.