In 1973, Jack Coleman was working as a ditch digger in Atlanta. One day, after finishing his shift, he got in his car to drive home. He stopped at a gas station, went to the men’s room and emerged wearing a business suit.

In 1973, Jack Coleman was working as a ditch digger in Atlanta. One day, after finishing his shift, he got in his car to drive home. He stopped at a gas station, went to the men’s room and emerged wearing a business suit.

As John R. Coleman, he continued on his way north to Pennsylvania, where he held another job: chairman of the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Later the same year, after working on a garbage truck in a Maryland suburb of Washington, he returned to Haverford, Pa., where he held yet another job: president of Haverford College.

Mr. Coleman wrote about his life as an undercover laborer — which also included a stint as a short-order cook in Boston — in a well-received 1974 book, “Blue-Collar Journal: A College President’s Sabbatical.”

It touched on his primary academic interest, the economics of labor, and marked another chapter in a varied life that took him from Canada to the University of Chicago and MIT, from India to a Texas prison yard, from college president to Vermont innkeeper.

“There’s a restlessness in me,” Mr. Coleman explained in 1987, “a desire to walk in other people’s shoes.”

Mr. Coleman was 95 when he died Sept. 6 at a hospital in Washington. He had complications from Parkinson’s disease, said a son, Steve Coleman.

Early in his career, Mr. Coleman — who went by “Jack” and did not use the title “Dr.,” even though he had a PhD — taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1953, he co-wrote an economics book with a colleague, George P. Shultz, who later became the labor secretary, treasury secretary and secretary of state. Mr. Coleman later collaborated on a book with Nobel laureate Paul A. Samuelson.

In the early 1960s, Mr. Coleman worked for the Ford Foundation in India and was the host of two educational series on economics that were carried by hundreds of television stations. He became president of Haverford, then a private men’s college of fewer than 1,000 students, in 1967.

During a turbulent era on campuses, Mr. Coleman was seen as a sympathetic figure by many of his students. He often ate with them in dining halls and invited them to the president’s house for informal visits.

When he issued a ruling that allowed students with long hair and beards to compete in sports, the college’s tennis coach quit in protest. Two weeks before Haverford’s football season was to begin in 1972, Mr. Coleman canceled the program because there were too few players to field a team. (The school’s store still sells T-shirts reading “Haverford Football: Undefeated Since 1971.”)

Despite leading such a small school, Mr. Coleman became a national force, as he led an effort to have dozens of college presidents sign a letter protesting U.S. military involvement in Southeast Asia.

In May 1970, he called off classes to lead 700 Haverford students and faculty members on a trip to Washington for an antiwar demonstration. But when a student wanted to burn the U.S. flag on campus, Mr. Coleman — a Canadian immigrant proud of his U.S. citizenship — devised a less provocative solution. He brought out a washtub in which the flag could be scrubbed in a symbolic cleansing of the nation’s ills.

Mr. Coleman’s greatest battle at Haverford was his effort to have women admitted to the college. He believed men’s schools were “morally indefensible,” but he could see reasons that women might want to have separate schools, such as Bryn Mawr College, Haverford’s neighbor.

Tense meetings were held with the boards of both colleges, as Mr. Coleman proposed measures that would allow women to enter Haverford as full-time students. His ideas were rejected in January 1977, and Mr. Coleman immediately announced his resignation.

Just three years later, he was vindicated when Haverford became fully coeducational.

One of the things Mr. Coleman emphasized was education beyond the classroom. He was an early advocate of the “gap year” between high school and college and recommended that students travel or work at challenging jobs.

Following his own advice, he took a sabbatical in the spring semester of 1973 to hold a series of blue-collar jobs, including ditch digger, garbageman and cook. (He worked briefly as a dishwasher but was fired.)

He enjoyed the camaraderie of his fellow workers, but as he wrote in “Blue-Collar Journal,” he also became aware of “how much isolation there is in all our lives.” While hauling garbage, Mr. Coleman was routinely ignored or insulted by the people whose trash he picked up. All it took to brighten his day was a word of thanks.

Once, in a moment of discouragement at Haverford, Mr. Coleman was thinking of stepping down from his job as president when a student walked into his office, Mr. Coleman wrote in “Blue-Collar Journal.”

The student “had no reason so far as I know to be aware that I was thinking of chucking it all. He said only one thing and left: ‘I think you’re doing a great job.’ ”

John Royston Coleman was born June 24, 1921, in Copper Cliff (now Sudbury), Ontario. He grew up in a factory town where his father was the superintendent of a smelting plant.

Mr. Coleman graduated from the University of Toronto’s Victoria College in 1943, then served in the Canadian navy during World War II.

He studied economics in graduate school at the University of Chicago, receiving a master’s degree in 1949 and a doctorate in 1950. After teaching at MIT until 1955, he spent a decade at what is now Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

During the 1970s, while serving as Haverford’s president, Mr. Coleman was also chairman of the board of governors of Philadelphia’s Federal Reserve Bank. He published six books on economics, in addition to “Blue-Collar Journal,” which was the basis for a 1976 TV movie starring Ralph Waite.

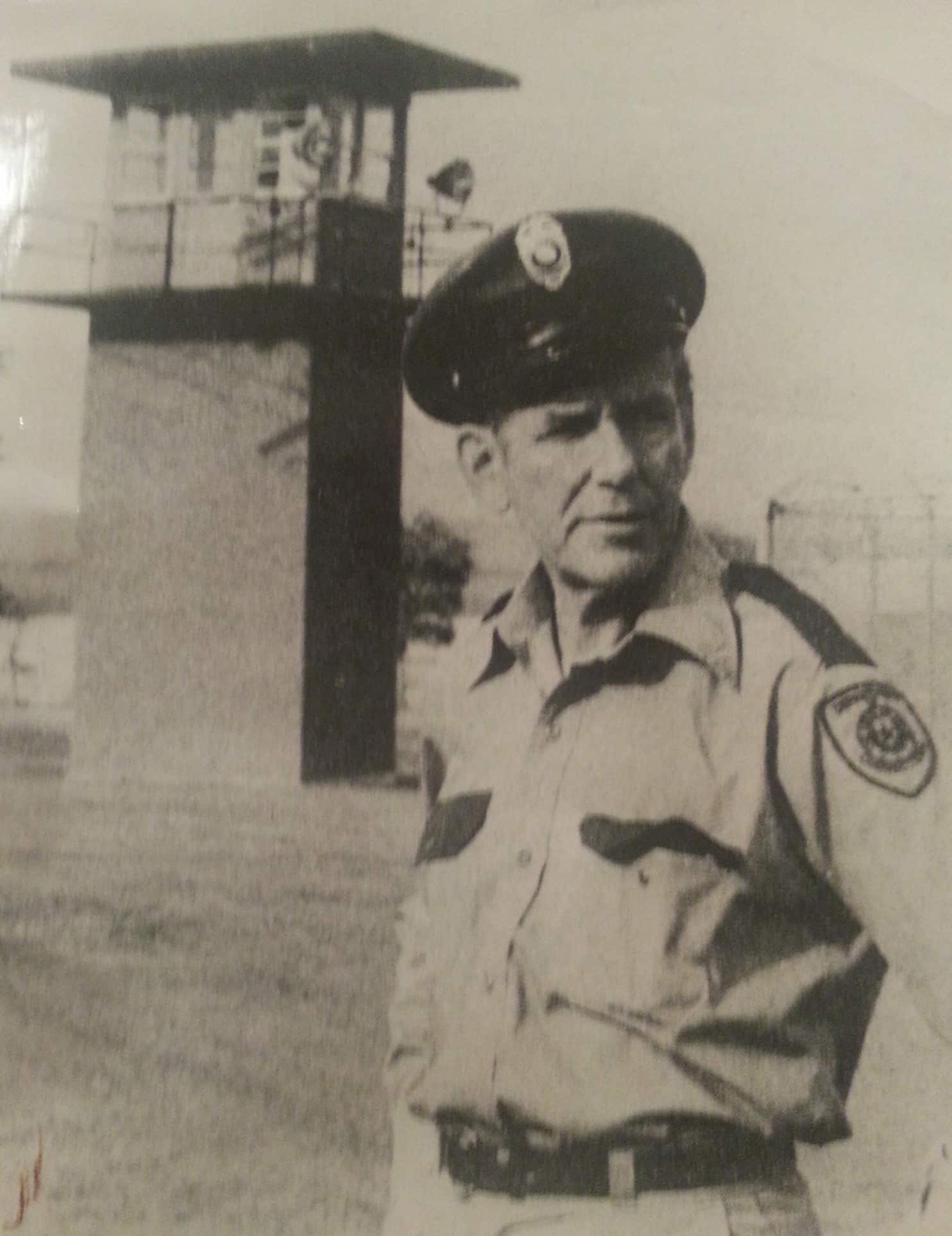

After Haverford, Mr. Coleman was president of the New York-based Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, where he worked on prison reform and other social issues. As an outgrowth of his work, he continued to go undercover in various guises, including as a prison inmate in three states and as a sewage worker, miner and Texas prison guard.

During a brutal cold snap in January 1983, Mr. Coleman spent 10 days on the streets of New York to learn what it was like to be homeless. He endured physical assaults and wrote about the experience in a cover story for New York magazine. Most degrading of all was his treatment at a city-run shelter “devoid of any graces at all.”

When he asked a question, he was told, “Don’t ask questions, I said. You’re not nobody.”

Mr. Coleman’s marriage to Mary Irwin, with whom he had five children, ended in divorce. A second marriage, to Elizabeth Terry, also ended in divorce.

Survivors include three children, John M. Coleman of Moorestown, N.J., Nancy J. Coleman of Topsham, Maine, and Stephen W. Coleman of the District; and seven grandchildren.

A son, Paul R. Coleman, died in 1996; a daughter, Patty A. Coleman, died in 2008.

In 1986, Mr. Coleman sold his New York apartment and bought an inn with 37 guest rooms on seven acres of land in Chester, Vt. He and a son restored the property, which he called the Inn at Long Last. Mr. Coleman enjoyed the collegial life of an innkeeper, especially cooking breakfast for guests.

He started a theater guild in Chester, acted in community productions and published a weekly newspaper for 10 years. In 2000, while serving as a justice of the peace in Vermont, he performed one of the country’s first legally recognized same-sex civil unions.

The central lesson he learned from his various experiences, Mr. Coleman said, was the importance of human dignity.

“Each of us has a unique quality, a worth,” he said in 1987. “I get struck by how easily we lose that. Next to love, dignity is my favorite word now.”