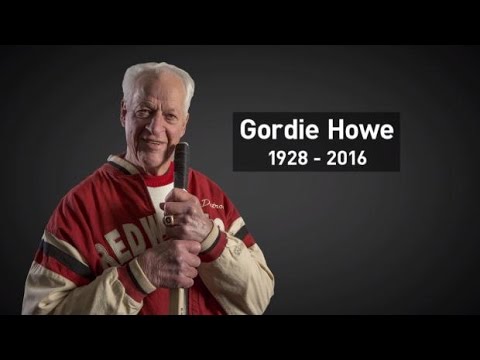

Gordie Howe, widely regarded as the most complete player in the sport’s history — and considered an ironman in many respects both on and off the ice — has died at age 88.

Gordie Howe, widely regarded as the most complete player in the sport’s history — and considered an ironman in many respects both on and off the ice — has died at age 88.

Born in Floral, Sask., Howe spent most of his time with the NHL’s Detroit Red Wings and played an unparalleled 33 seasons over six decades after breaking into the pro ranks in 1945.

Howe’s health had deteriorated, and he had suffered a series of strokes in recent years, fighting to recoup his health time and again after each setback.

A statement from his family said he passed away “peacefully… with his family by his side.”

Howe’s sister, Saskatoon resident Helen Cummine, told the CBC that Dr. Murray Howe, the hockey great’s youngest of four children with longtime love, the late Colleen Howe, was with his father when he passed away at the Ohio radiologist’s home on Friday morning.

“I guess he didn’t want to fight anymore, but what a fight he had,” Cummins said.

Career spanned 6 decades.

As a player, longevity and productivity were Howe’s hallmarks. No one proved more durable.

As a teenager, he started his pro career with the Omaha Knights of the United Hockey League. He ended it by skating one final shift for the Detroit Vipers of the International Hockey League in 1997 — at age 69.

In between, he spent 25 seasons with the Red Wings and six more in the rival World Hockey Association before returning to the NHL for one last hurrah with the Hartford Whalers.

Howe retired in 1980 as the NHL leader in career goals (801) and career points (1,850)—both records were later broken by Wayne Gretzky, who considered Howe his idol. However, Howe always maintained his string of 20 straight seasons as one of the league’s top five scorers during his Hall of Fame career.

Howe now ranks fourth on the NHL’s all-time points list after being surpassed by Mark Messier and, this past season, Jaromir Jagr. , Hwe’lllranks second all-time in goals.

Gretzky raised the bar statistically. B t it was Howe who set the standard for consistency.

“I met him when I was 10,” Gretzky recalled. “And when you’re 10 years old, you often meet your idol, and they’re not as nice or as big as you think … I was lucky that I picked the right person to look up to.”

A post on Gretzky’s Twitter account called Howe “the greatest hockey player ever” and “the nicest man I have ever met.”

Such was Howe’s personality, as glaringly different as it was from his hockey persona.

Howe, the man, was charming—soft-spoken, at times shy, with a self-deprecating sense of humour and an easy laugh.

When current Red Wings owner Mike Ilitch named one of the entranceways into Joe Louis Arena after him, Howe told reporters after the presentation: “I said to Mr. Ilitch, ‘Before I go out there, I just want to make sure that it isn’t an exit.'”

On the other hand, Howe, the hockey player, was fearsome — a strapping winger with strong instincts, an efficient stride and a nastiness that belied his gentle nature off the ice.

Total package

Howe was a formidable winger blessed with brawn and the biggest elbows in the business. He was relentless in his pursuit of the puck, which, combined with his prodigious strength and stamina, made him a force to be reckoned with in the corners and sweep through the slot.

Already an immaculate passer, he strived to develop a more powerful wrist shot and, in 1952-53, became the first NHL player to reach the 90-point plateau with 95 points, including a career-best 49 goals.

Howe hit 40-plus goals five times with Detroit and notched a career-high 103 points in 1968-69, partnered with Alex Delvecchio and Frank Mahovlich.

From 1949 to 1971, he never scored fewer than 23 goals per season. At 41, he had 44 go ls for Detroit. At 46, he earned WH MVP honours with a 31-goal, 100-point campaign for the Houston Aeros. At 52, he was still robust and respected, and he had 41 points in 80 games in that final NHL season with Hartford.

Howe was the total package — an all-around talent and 21-time NHL all-star.

Howe’s career nearly ended in the opening game of the 1950 playoffs when he tried to throw a body check at Toronto’s Ted (Teeder) Kennedy. Howe s ammed so hard into the boards that he was knocked unconscious and, bleeding profusely, removed from the ice on a stretcher. Howe suffered a frac ured skull and underwent surgery to relieve the pressure from his brain before making a full recovery. He returned the next season to win the scoring title by 20 points over Montreal’s Maurice (Rocket) Richard.

Howe was a dominant presence as Detroit hoisted the Stanley Cup four times in six seasons in the 1950s, teaming with Sid Abel and Ted Lindsay to form the Motor City’s aptly named Production Line.

Lindsay once claimed that Howe worried needlessly about losing his place on the teams he played on (as a rookie, he kept a scrapbook to show others that he played in the NHL) and that neither six Hart trophies as NHL MVP nor six Art Ross trophies as scoring champion soothed Howe’s feelings of insecurity.

Or so the story goes.

Howe figured he had to fight to establish himself early in his career and scrapped plenty, scoring a one-punch knockout of Richard in his first game at Montreal. But he eventually reali ed that he couldn’t score goals from the penalty box, so he heeded the advice of Red Wings head coach Jack Adams, who told him not to turn his back on a fight but not to go looking for one, either.

Howe fought selectively after that, preferring to deliver the devastating elbows for which he became most famous. Yet such was Howe’s r putation that, to this day, his name remains synonymous with fighting: score three goals, and, in modern hockey parlance, it’s a hat trick: get a goal, an assist, and into a fight, and it’s a “Gordie Howe” hat trick.

Played with sons in WHA

Hampered by an arthritic left wrist, Howe retired from the NHL following the 1970-71 season. But two years into an unfulfilling tenure as a Red Wings vice president, the upstart WHA offered him a unique hat trick—the opportunity to play in Houston alongside sons Mark and Marty.

Howe had the wrist surgically repaired, signed with the Aeros and starred for six seasons in the WHA (he had 174 goals and 508 points in 419 games) before it merged with the NHL in 1979.

One final season with the Whalers in 1979-80 (ironically, Gretzky’s first in the NHL) and one last shift with the minor-league Vipers in 1997-98 to earmark six decades as a pro player and Howe hung up his skates — for good, this time — on Oct. 3, 1997.

Howe spent much of his retirement making personal appearances and being involved with charitable ventures, notably the Howe Foundation. His charming demeanour, fondness for fans, and penchant for telling funny stories made him a popular public speaker and a frequent guest at hockey camps and sports memorabilia conventions.

“Some wise old man told me, ‘If someone is interested enough in you to ask for your autograph, you should be interested enough to sign it.

“I used to put two remembered years i my pocket and eat them after the game to give me a little boost because of the long lines. The staff would often open the door so cold air would come in to get rid of us because we would stay and sign autographs.”

Throughout his career and well into r tirement, Gordie’s wife of 56 years handled the family finances. She built the Howe brand under the company label Power Play International until Colleen Howe was stricken with Pick’s disease, a rare brain illness associated w th dementia.

“She was the sole initiator for everything in the relationship,” said Murray Howe.

With his wife’s death in March 2009, Howe became a vocal crusader for dementia, Alzheimer’s and similar conditions, establishing the Gordie and Colleen Howe Fund for Alzheimer’s in partnership with Baycrest — a facility dedicated to aging and brain health operated out of the University of Toronto.

Howe struggled with cognitive impairment and short-term memory loss later in life.

May the memories of Mr. Hockey be everlasting.

Source: CBC