JOHANNESBURG (A.P.) — Desmond Tutu, South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning icon, an uncompromising foe of the country’s past racist policy of apartheid, and a modern-day activist for racial justice and LGBT rights, died Sunday at 90. South Africans, world leaders, and people around the globe mourned the death of the man viewed as the country’s moral conscience.

Tutu worked passionately, tirelessly, and non-violently to tear down apartheid — South Africa’s brutal, decades-long regime of oppression against its Black majority that only ended in 1994.

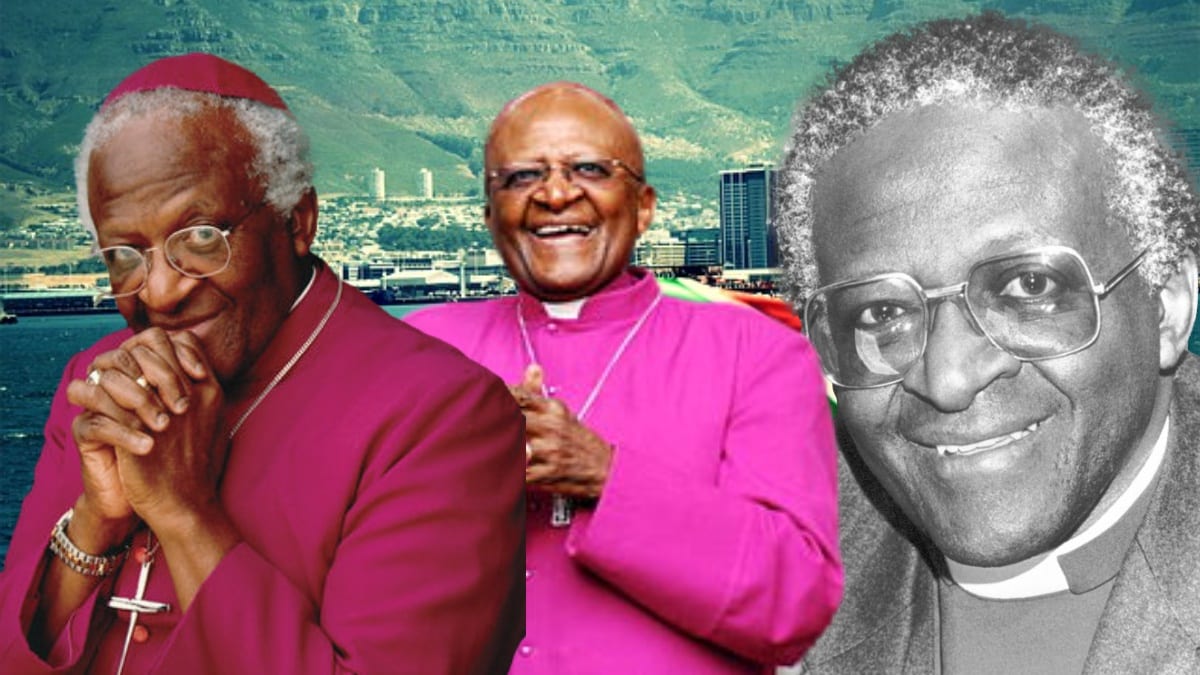

The buoyant, blunt-spoken clergyman used his pulpit as the first Black bishop of Johannesburg and later the Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town and frequent public demonstrations to galvanize public opinion against racial inequity, both at home and globally.

Nicknamed “the Arch,” Tutu was diminutive and had a playful sense of humour but became a towering figure in his nation’s history. He was comparable to fellow Nobel laureate Nelson Mandela, a prisoner during white rule who became South Africa’s first Black president. Tutu and Mandela shared a commitment to building a better, more equal South Africa.

Upon becoming president in 1994, Mandela appointed Tutu to be chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which uncovered the abuses of the apartheid system.

Tutu’s death on Sunday “is another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa,” South African President Cyril Ramaphosa said.

“From the pavements of resistance in South Africa to the pulpits of the world’s great cathedrals and places of worship and the prestigious setting of the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony, the Arch distinguished himself as a non-sectarian, inclusive champion of universal human rights.”

Tutu died peacefully at the Oasis Frail Care Center in Cape Town, the Archbishop Desmond Tutu Trust said Sunday. He had been hospitalized several times since 2015 after being diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1997.

“Typically, he turned his misfortune into a teaching opportunity to raise awareness and reduce the suffering of others,” said the Tutu Trust. “He wanted the world to know that he had prostate cancer and that the sooner it is detected, the better the chance of managing it.”

He and his wife, Leah, lived in a retirement community outside Cape Town in recent years.

“His legacy is moral strength, moral courage, and clarity,” Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town Thabo Makgoba said in a video statement. “He felt with the people. In public and alone, he cried because he felt people’s pain. And he laughed — not just laughed, he cackled with delight — when he shared their joy.”

A seven-day mourning period is planned in Cape Town before Tutu’s burial, including a two-day lying in state, an ecumenical service, and an Anglican requiem mass at St. George’s Cathedral in Cape Town to church officials. To mark his death, we will light Cape Town’s landmark Table Mountain in purple, the colour of Tutu’s robes as archbishop.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson was among the world leaders paying tribute to Desmond Tutu. “He was a critical figure in the fight against apartheid and the struggle to create a new South Africa — and will be remembered for his spiritual leadership and irrepressible good humour.”

Desmond Mpilo Tutu Oct. 77 October. Dec. 26, 2021)

Throughout the 1980s — when South Africa was gripped by anti-apartheid violence and a state of emergency giving police and the sweeping military powers — Tutu was one of the most prominent Black leaders able to speak out against abuses.

A lively wit lightened Tutu’s hard-hitting messages and warmed otherwise grim protests, funerals, and marches. He was a formidable force short, brave, and tenacious, and apartheid leaders learned not to discount his canny talent for quoting apt scriptures to harness moral support for change.

The Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 highlighted his stature as one of the world’s most effective champions for human rights, a responsibility he took seriously for the rest of his life.

With the end of apartheid and South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, Tutu celebrated the country’s multi-racial society, calling it a “rainbow nation,” a phrase that captured the heady optimism of the moment.

In 1990, after 27 years in prison, Mandela spent his first night of freedom at Tutu’s residence in Cape Town. Later, Mandela called Tutu “the people’s archbishop.”

Tutu also campaigned internationally for human rights, especially LGBT rights and same-sex marriage.

“I would not worship a God who is homophobic, and that is how deeply I feel about this,” he said in 2013, launching a campaign for LGBT rights in Cape Town. “I would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven. No, I would say, ‘Sorry, I would much rather go to the other place.'”

Desmond Tutu said he was “as passionate about this campaign (for LGBT rights) as I ever was about apartheid. For me, it is at the same level.” He was one of the most prominent religious leaders to advocate LGBT rights.

Tutu’s very public stance on LGBT rights put him at odds with many in South Africa across the continent and within the Anglican church.

Tutu said South Africa was a “rainbow” nation of promise for racial reconciliation and equality, even though he grew disillusioned with the African National Congress, the anti-apartheid movement that became the ruling party in the 1994 elections. His outspoken remarks long after apartheid sometimes angered partisans who accused him of being biased or out of touch.

Tutu was particularly incensed by the South African government’s refusal to grant the Dalai Lama a visa. This prevented the Tibetan spiritual leader from attending Tutu’s 80th birthday celebration and a planned gathering of Nobel laureates in Cape Town. South Africa rejected Tutu’s accusations of bowing to pressure from China, a major trading partner.

Early in 2016, Desmond Tutu defended the reconciliation policy that ended white minority rule amid increasing frustration among South Africans who felt they had not seen the expected economic opportunities and other benefits since apartheid ended. Tutu chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, investigated atrocities under apartheid, and granted amnesty to some perpetrators. Still, some people believe the law should have prosecuted more former white officials.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu Oct. 7rn Oct. 7, 1931, in Klerksdorp, west of Johannesburg, became a teacher before entering St. Peter’s Theological College in Roseville in 1958 to train as a priest. He was ordained in 1961 and became chaplain at the University of Fort Hare six years later.

Moves to Lesotho and Britain’s tiny southern African kingdom followed, with Tutu returning home in 1975. He became bishop of Lesotho, chairman of the South African Council of Churches, and, in 1985, the first Black Anglican bishop of Johannesburg, and then in 1986, the first Black Archbishop of Cape Town. He ordained women priests and promoted gay priests.

Tutu was arrested in 1980 for participating in a protest, and his passport was confiscated for the first time. He got it back for trips to the United States and Europe, where he held talks with the U.N. secretary-general, the pope, and other church leaders.

Tutu called for international sanctions against South Africa and discussed ending the conflict.

Tutu often conducted funeral services after the massacres that marked the negotiating period of 1990-1994. He railed against black-on-black political violence, asking crowds, “Why are we doing this to ourselves?” In one powerful moment, Tutu defused the rage of thousands of mourners in a township soccer stadium after the Boipatong massacre of 42 people in 1992, leading the crowd in chants proclaiming their love of God and themselves.

As head of the Truth Commission to promote racial reconciliation, Desmond Tutu and his panel listened to harrowing testimony about torture, killings, and other atrocities during apartheid. At some hearings, Tutu wept openly.

“Without forgiveness, there is no future,” he said then.

The commission’s 1998 report laid most of the blame on the forces of apartheid but also found the African National Congress guilty of human rights violations. The ANC sued to block the document’s release, earning a rebuke from Tutu. “I didn’t struggle to remove one set of those who thought they were tin gods to replace them with others who are tempted to think they are,” Tutu said.

In July 2015, Tutu renewed his 1955 wedding vows with his wife, Leah. In a church ceremony, the Tutus’ four children and other relatives surrounded the elderly couple.

“You can see that we followed the biblical injunction: We multiplied, and we’re fruitful,” Desmond Tutu told the congregation. “But all of us here want to thank you … We knew that without you, we are nothing.”

Tutu is survived by his wife of 66 years and their four children.

Asked once how he wanted to be remembered, he told The Associated Press: “He loved. He laughed. He cried. He was forgiven. He forgave. He was greatly privileged.”

___

A.P. journalist Christopher Torchia contributed to this report.

Andrew Meldrum, The Associated Press

UN chief calls Desmond Tutu ‘an inspiration to generations

Reactions to the death Sunday of Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former Archbishop of Cape Town Desmond Tutu:

“Archbishop Tutu was a towering global figure for peace and an inspiration to generations across the world. During the darkest days of apartheid, he was a shining beacon for social justice, freedom, and non-violent resistance. … Although Archbishop Tutu’s passing leaves a huge void on the global stage. In our hearts, we will be forever inspired by his example to continue the fight for a better world for all.” — U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres.

___

“Archbishop Desmond Tutu was a mentor, a friend, and a moral compass for me and so many others. A universal spirit, Archbishop Tutu was grounded in the struggle for liberation and justice in his own country and concerned with injustice everywhere. He never lost his playful sense of humor and willingness to find humanity in his adversaries, and Michelle and I will miss him dearly.” — Former U.S. President Barack Obama.

“I remember with fondness my meetings with him and his great warmth and humor,” the tweet from Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II on The Royal Family site said. “Archbishop Tutu’s loss will be felt by the people of South Africa, and by so many people in Great Britain, Northern Ireland, and across the Commonwealth, where he was held in such high affection and esteem.”

___

“The death of Archbishop Desmond Tutu (always known as Arch) is news that we receive with profound sadness — but also with profound gratitude as we reflect upon his life. … Arch’s love transformed the lives of politicians and priests, township dwellers and world leaders. The world is different because of this man.” — Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby.

___

“Indeed, the big baobab tree has fallen. South Africa and the mass democratic movement has lost a tower of moral conscience and an epitome of wisdom.” — The African National Congress, South Africa’s ruling party.

___

“The friendship and the spiritual bond between us was something we cherished. Archbishop Desmond Tutu was entirely dedicated to serving his brothers and sisters for the greater common good. He was a true humanitarian and a committed advocate of human rights.” — the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader.

___

“I am deeply saddened to hear of the death of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. He was a critical figure in the fight against apartheid and the struggle to create a new South Africa — and will be remembered for his spiritual leadership and irrepressible good humor.” — British Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

___

“No words better exemplify his ministry than the three he contributed to a work of art at The Carter Center: love, freedom, and compassion. He lived his values in the long struggle to end apartheid in South Africa, in his leadership of the national campaign for truth and reconciliation, and his role as a global citizen. His warmth and compassion offered us an eternal spiritual message.” — former U.S. President Jimmy Carter.

___

“He was never afraid to call out human rights violators no matter who they were, and his legacy must be honored by continuing his work to ensure equality for all.” — Amnesty International South Africa Executive Director Shenilla Mohamed.

___

“The loss of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Mpilo Tutu is immeasurable. He was larger than life, and his life has been a blessing for so many in South Africa and around the world. His contributions to struggles against injustice, locally and globally, are matched only by the depth of his thinking about the making of liberatory futures for human societies.” — The Nelson Mandela Foundation.

___

“I’m saddened to learn of the death of global sage, human rights leader, and powerful pilgrim on earth. … A great, influential elder is now eternal, witnessing ancestor. And we are better because he was here.” — Dr. Bernice King, youngest daughter of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

___

“We are all devastated at the loss of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Without his passion, commitment, and keen moral compass, the Elders would not be who they are today. He inspired me to be a ‘prisoner of hope in his inimitable phrase. The arch was respected worldwide for his dedication to justice, equality, and freedom. Today we mourn his death but affirm our determination to keep his beliefs alive.” — Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland and chair of The Elders, an independent group of world leaders and human rights activists.

___

Tutu’s passing “closes an important chapter in Africa’s long and painful struggle for justice, liberty, and democracy and the continent’s current efforts to create prosperity and stand to find its competitive edge in the rest of the world. For South Africans, it is a major reckoning with the reality that one-by-one, its heroic liberators are leaving.” — Raila Odinga, Kenya’s former prime minister, and opposition leader.

___

“His legacy is moral strength, moral courage, and clarity. He felt with the people. In public and alone, he cried because he felt people’s pain. And he laughed — no, not just laughed, he cackled with delight — when he shared their joy.” — Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town Thabo Makgoba.

___

“His Holiness Pope Francis was saddened to learn of the death of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and he offers heartfelt condolences to his family and loved ones. Mindful of his service to the Gospel through the promotion of racial equality and reconciliation in his native South Africa, His Holiness commends his soul to the loving mercy of Almighty God.” — Telegram sent by the Vatican secretary of state, Cardinal Pietro Parolin.

___

“A powerful and courageous voice for nonviolence, reconciliation, and peace. He will be very much missed in our troubled world. May he Rest In Peace.” — Egypt’s former vice president and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Mohamed ElBaradei.

___

“Through his distinguished work over the years as a cleric, freedom fighter, and peacemaker, Archbishop Tutu inspired a generation of African leaders who embraced his non-violent approaches in the liberation struggle.” — Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta.

___

Tutu’s death was “a loss for justice, truth, and peace in the world. … He loved Palestine and Palestine loved him.” — Mohammed Shtayyeh, prime minister of the Western-backed Palestinian Authority.