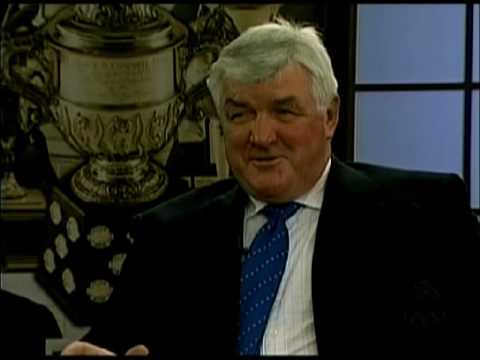

Pat Quinn, who passed away at age 71 after a lengthy illness in Vancouver General Hospital on Sunday, was many things to many people.

Pat Quinn, who passed away at age 71 after a lengthy illness in Vancouver General Hospital on Sunday, was many things to many people.

He dearly will be missed. He touched plenty of lives and that was easy to see on Monday when all the tributes rolled in.

“Pat’s impact on our city has been immeasurable,” said Trevor Linden, the president of hockey operations for the Vancouver Canucks. Linden played for Quinn when coached the team from 1990-91 to 1995-96, including a Stanley Cup finals appearance in 1993-94. “He was responsible for bringing hockey to the forefront in Vancouver. He brought the pride back to the Canucks and today his fingerprints and impact are still felt within this organization.”

When friends ask me about my favourite people I’ve dealt with as a sports reporter, Quinn easily is mentioned in my top five, even though we had our battles. When the Toronto Maple Leafs struggled late in the 2005-06 campaign, Quinn’s final season in Toronto, I was critical of his team. So he scolded me in a post-game press conference one night. He refused to answer my forgettable question.

“I’m not answering that,” he said. “You’re always running down my team.”

This sort of reaction was infrequent. I know he had run-ins with some of my colleagues in the Vancouver, but he was pure class in Toronto. He always stayed until the last question was asked in his post-game pressers and post-practice scrums. I think he enjoyed the give and take with most reporters.

‘I caught him with my shoulder’

I never learned more about the game or enjoyed a coach’s company around the rink as my time with Quinn.

First and foremost, he was so smart. He was an excellent conversationalist. Quinn would often get asked about his bone-crushing hit on Bobby Orr in 1969.

Quinn always wanted to put the incident into perspective. He pointed out that the two defencemen had some prior run-ins leading up to the hit.

One in particular saw Orr slash Toronto goalie Bruce Gamble when he covered the puck in a prior game. This resulted in Quinn knocking down Orr with a cross check. While on his back Orr kicked Quinn in the stomach. Quinn retaliated with a boot to Orr’s behind.

On the well-known hit, Quinn gave credit to his teammate Brit Selby, who usually was assigned to check Orr. Selby was alongside Orr as he carried the puck along the sideboards in his own end. His attention was directed at Selby and didn’t see Quinn skating in to lower the boom.

“I caught him with my shoulder,” said Quinn, who was accused at the time of catching Orr with an elbow.

“It wasn’t an elbow. If my elbow hit him, maybe it was a momentum thing,” he added with a sly smile.

Quinn had wonderful sense of humour.

Hated Nassau Coliseum

One day after a morning skate at the Nassau Coliseum, the home of the New York Islanders, we were walking out of the building and across to the parking lot to the hotel. He told me he hated the place. I asked why?

“Leon Stickle,” he said.

“Why him,” I asked Quinn of the highly-regarded linesman.

“You don’t know about the 1980 final?” Quinn retorted. “I thought you knew your hockey history.”

Stickle missed an offside call on a Duane Sutter goal that gave the Islanders a 4-4 tie late in Game 6. Quinn’s Flyers eventually lost that contest in overtime and watched the Islanders celebrate their first of four consecutive Stanley Cup championships that night.

Quinn always seemed to have a gripe with on-ice officials. A few Maple Leafs once told me that they felt the referees never gave Toronto a fair shake because of Quinn’s constant complaints.

I asked the coach about this theory and he didn’t agree. Then a few years later, I read Mike Johnston and Ryan Walter’s book, Simply the Best: Insights and Strategies from Great Hockey. The two interviewed all of the great coaches, including Claire Drake, Scotty Bowman, Roger Neilson and Quinn.

In Quinn’s chapter, he said: “Right now, I’m upset with the officiating and how we get treated. People say you get special favour in Toronto, but in reality it works the opposite way.

“Yet all my bitching just hurts us more, really. When I get upset with what’s going on, I’m not a good example for the guys, because then I speak about it and then I’m giving our guys an excuse.”

I couldn’t wait to see Quinn to bring this subject up. When I did, he chuckled and told me “timing is everything.”

Hamilton roots

You couldn’t help but appreciate his verbal shots. When I left the Toronto Sun for a brief 10-month stint in the NHLPA communications department only to return to the business with the Globe and Mail, Quinn told me he once delivered the newspaper in Hamilton.

“I didn’t make any money,” he said. “It was about as popular in those days as it is now. I couldn’t get enough homes to deliver it to.”

Quinn was a proud Canadian and extremely proud of his family as well as his hometown of Hamilton. They called him the Big Irishman and he was, but his family’s roots actually were from Liverpool, England.

Quinn loved to tell stories about his father, Jack, and the blue-collar neighbourhood he was raised in East Hamilton called Mahoney Park. It meant a lot to Quinn when the street he grew up on, Glennie Avenue, was renamed Pat Quinn Way after he coached Canada to 2002 Olympic gold in Salt Lake City.

Jack was a hockey player, but a better football player. He captained the 1919 Hamilton Tigers to the Grey Cup championship. He later became a firefighter and head of the local firefighter’s union. Quinn’s sister was a police officer.

Interesting fact: Quinn passed away on the same weekend as former NHLer Murray Oliver and Soviet Union national team coach Viktor Tikhonov. Quinn admired Tikhonov and the Russian-style of hockey. Oliver was one of Quinn’s first hockey heroes growing up in Hamilton. The two later played together on the Maple Leafs.

Maybe the Hamilton Tiger-Cats can follow up on Sunday with a win at the Grey Cup in Vancouver, Quinn’s final resting place. I know there would be one larger-than-life fellow upstairs who would appreciate the victory.