Diego Maradona, the mop-haired boy from a Buenos Aires slum who dribbled and dazzled his way to world fame, becoming one of the greatest soccer players of all time but also one of the most self-destructive, has died.

Maradona died on Wednesday from a heart attack; the Associated Press confirmed that he chased with such fury never far from the spotlight. Maradona had recently been plagued by health issues, recently suffering a subdural hematoma, which required brain surgery.

As the news of Maradona’s death circulated the world Wednesday, Argentine President Alberto Fernandez called for three days of national mourning while UEFA, soccer’s governing body in Europe, announced there would be a minute of silence before its Champions League and Europa League games this week.

Soccer stars, past and present, took to social media to say goodbye.

Pele, the Brazilian legend and perhaps the greatest player of all time, wrote on Twitter that he “lost a great friend and the world lost a legend. … One day, I hope we can play ball together in the sky.”

Cristiano Ronaldo, the five-time world player of the year from Portugal who currently stars for Juventus, tweeted, “Today I say goodbye to a friend, and the world says goodbye to an eternal genius.”

Like that other famous Argentine export, the tango, Diego Maradona brought flair, passion, and an undeniable sense of darkness to his sport and life. Few could match his artistry, skill, and creativity on the field, but he could also be a devious, angry player. He was a volatile man of prodigious appetites whose excesses often landed him in the hospital off the field.

During a professional career that began on a Buenos Aires field when he was 15, Maradona scored hundreds of goals, many of them the legend’s stuff, including two in a single match against England in the 1986 World Cup.

The first is considered by many the most notorious goal in the history of the sport, and the second among the most celebrated.

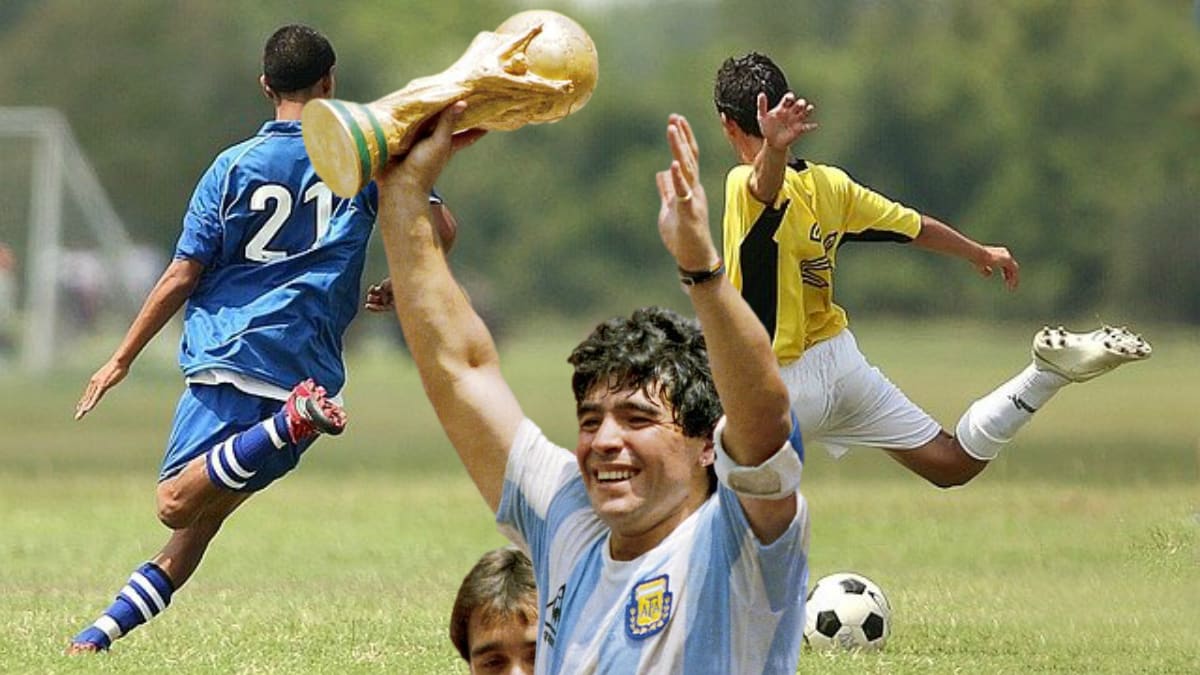

His career reached its summit when he led Argentina’s national team to victory in the 1986 World Cup. But drug abuse and other self-destruction act tainted his final years as a player, and he retired in 1997, just a whisper of his former self.

Diego Maradona played 91 games for the Argentine national team and was a star for Italy and Spain teams. He played his last World Cup game in Foxboro, Mass., in 1994, escorted off the field for a drug test he would fail.

One of eight children of a laborer who had migrated to the city from rural Corrientes province, Maradona was born Oct. 30, 1960, in a “villa miseria,” or slum, in the suburban Buenos Aires community of Villa Fiorito. The family lived in abject poverty.

In his autobiography, “I Am El Diego,” he recalled walking to school, kicking a ball along streets, upstairs, and railroad tracks. He spent hours playing pickup games in a nearby horse pasture.

When he was 9, a friend invited him to a tryout at the Argentinos Juniors, an adult professional soccer team. He impressed enough to earn a spot on the Cebollitas, or Little Onions, a feeder club for the team.

The Little Onions would go on to win 136 games without defeat, with young Maradona often scoring three or more goals a game.

By the time he was 12, he had worked at professional games as a ball boy, becoming a favorite of the crowds for his halftime juggling skills. A television variety show invited him to show off his talents, and in soccer-mad Argentina, he became a minor celebrity.

Just a few days before his 16th birthday, the coach of Argentinos Juniors brought him onto the first team. He first stepped onto the field as a substitute, with the coach telling him, “Go, Diego, and play like you know how to play. And if you can dribble through someone’s legs.” Minutes later, the young Maradona did just that.

“That day,” he said later in his autobiography, “I felt like I touched heaven with my hands.”

Leading Argentine teams began a bidding war for his services. Diego Maradona moved his family out of Villa Fiorito to an apartment. Eventually, he joined the famed Boca Juniors team.