The 92-Year-Old Michigan Democrat Michigan Democrat John Dingell Jr. was the longest-serving member of the United States Congress in history. He helped write most of the nation’s major environmental and energy laws. Dingel died Thursday, February 7, 2019, his wife said.

Dingell died peacefully at his home in Dearborn, surrounded by his wife, U.S. Rep. Deborah Dingell.

The statesman from Dearborn Michigan was a champion of the auto industry and was credited with increasing access to health care, were among some of his accomplishments.

Quoting a statement from the late congressman wife’s office, “He was a lion of the United States Congress and a loving son, father, husband, grandfather, and friend.”

“He will be remembered for his decades of public service to the people of Southeast Michigan, his razor-sharp wit and a lifetime of dedication to improving the lives of all who walk this earth.”

About a year ago, the Democrat

News of his death prompted an outpouring online from lawmakers, former colleagues, and others — many of whom regularly enjoyed Dingell’s tweets.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer ordered U.S. and Michigan flags within the State Capitol Complex and on all state, buildings to be lowered to half-staff Friday in Dingell’s honor.

“Today, the great state of Michigan said farewell to one of our greatest leaders,” Whitmer said. “We are a stronger, safer, healthier nation because of Congressman Dingell’s 59 years of service, and his work will continue to improve the lives of Michiganders for generations to come.”

Sen. Debbie Stabenow, D-Lansing, said Dingell understood the connection Michiganians have to manufacture, agriculture, to the land and the Great Lakes.

“Congressman John Dingell — the Dean of the House and my dear friend — was not merely a witness to history. He was a maker of it,” Stabenow said.

“His original family name, translated into Polish, meant ‘blacksmith.’ Nothing could be more fitting for a man who hammered out our nation’s laws, forging a stronger union that could weather the challenges of the future. John Dingell loved Michigan.”

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-California, called Dingell “a beloved pillar of the Congress and one of the greatest legislators in American history.”

“John Dingell leaves a towering legacy of unshakable strength, boundless energy, and transformative leadership,” Pelosi said.

“Chairman Dingell was our distinguished Dean and Chairman, our legendary colleague and a beloved friend. His memory will stand as an inspiration to all who worked with him or had the pleasure of knowing him. His leadership will endure in the lives of the millions of American families he touched.”

Detroit News Publisher and Editor Jon Wolman said Dingell “was public service personified, a giant personality whose political ingenuity lasted until his final breath, or should I say his final tweet.”

“I never knew a better legislator or a stronger voice,” added Wolman, who knew Dingell from their time together in Washington and Detroit.

Influence etched in many ways.

Nicknamed “the Truck” and “Big John,” his given name graces the Veterans Administration hospital in Detroit, the road leading to Detroit Metropolitan Airport in Romulus and the Capitol Hill hearing room of the influential House Energy & Commerce Committee that he long chaired.

In a bid to fulfill his father’s dream, Dingell introduced national health insurance legislation every Congress until 2010, when his bill was turned into the controversial Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and signed into law by President Barack Obama.

Drawing on his love of the outdoors, Dingell became a lead champion of laws to protect the environment, including the creation of North America’s first international wildlife refuge along the Detroit River.

Major legislation that he helped become law include the National Wilderness Act in 1964 and the Water Quality Act in 1965, writing the Endangered Species Act in 1973, the Safe Drinking Water Act in 1974 and the Clean Air Act in 1990.

Dingell is survived by his wife, a Democrat who took over his congressional seat in 2015. Other survivors include three adult children from his first marriage: John III “Chip,” Christopher and Jennifer. His daughter, Jeanne, died three years earlier.

After he announced his retirement in early 2014, Obama described Dingell as “one of the most influential legislators of all time.” Later that year, Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the country.

Dingell cast more than 25,000 votes in his 59-year career. The one he said he was most proud of supported the 1964 Civil Rights Act, though it led to a brutal re-election fight — the second time Dingell had a cross burned on his lawn.

He cast his final primary vote Dec. 11, 2014, in favor of a $1.1 trillion spending bill that took months to negotiate and get through a deeply divided Congress.

Before his final vote, a measure to expand John Muir National Park in Martinez, California, Dingell was applauded by his House colleagues. Lawmakers took pictures as he placed his voting card into the slot for the final time.

“Honored to cast my final vote on behalf of the proud people of Michigan,” Dingell wrote on Twitter. “To this day, I consider myself the luckiest guy in shoe leather.”

Post-Congress career

Since leaving Congress, Dingell had built a reputation as a witty Twitter personality, with more than 258,000 followers. He often opined on President Donald Trump and University of Michigan football.

Dingell late last year published a book about his 59 years in the U.S. House, titled “The Dean: The Best Seat in the House” — a reference to his title as the member with the chamber’s longest record of service. It was co-written with David Bender.

In retirement, John formed a partnership with the University of Michigan, where he served as an unpaid guest lecturer and scholar in residence at the Dearborn campus. His mission was to inspire the next generation of civic leaders.

He donated 600 to 700 boxes of his congressional papers dating to 1955 to the University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library in Ann Arbor.

“Except John Quincy Adams,” said Steve Mitchell, an East Lansing-based Republican strategist and consultant, “there’s no one with longer participation in the affairs of the United States than John Dingell.”

Since his retirement, former staffers, colleagues, and friends would crowd into Debbie Dingell’s office in the Cannon House Office Building when he visited at the holidays. They wanted a chance to catch up with “The Dean” and wish him well.

Dingell served in World War II and credited President Harry Truman’s dropping of two atomic bombs on Japan with saving his life because he feared he wouldn’t survive an attempted invasion of the Asian island.

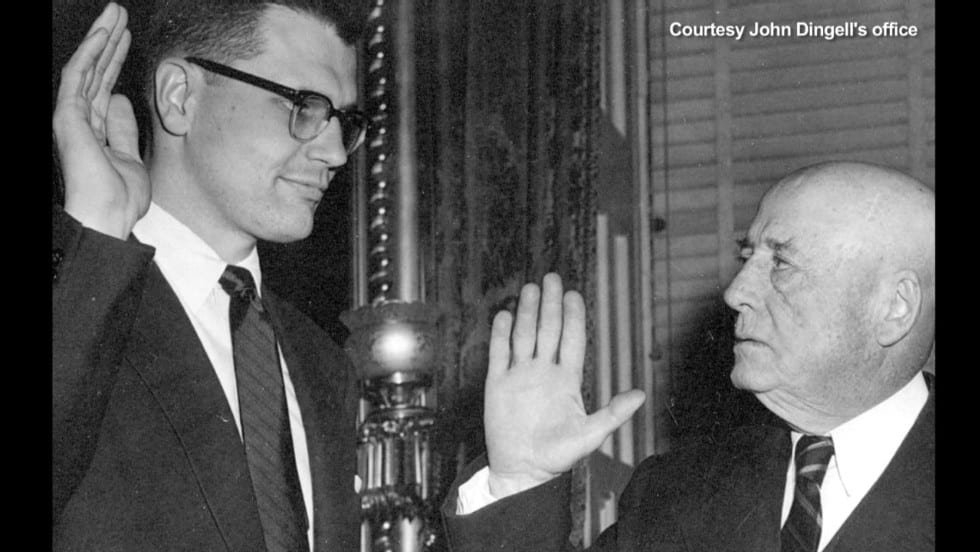

Dingell set his own measuring stick for history to judge him at age 29, following his election to fill the southeast Michigan congressional seat held by his father until his sudden death.

“My father loved and respected the House and all its members,” said Dingell, choking back tears after lawmakers paid tribute to his father on the House floor in January 1956. “If I can be half the man my father was, I shall feel I am a great success.”

Given the presidential honor and the list of laws bearing his name, Dingell appeared to achieve the goal.

“John Dingell always put the public interest ahead of everything else,” said James Blanchard, a Democrat and former two-term governor of Michigan who served with Dingell in the U.S. House.

Those who knew Dingell to say Dingell also measured his success by the happiness that he found in his marriage to the former Deborah Insley, a General Motors heiress who shared his passion for the auto industry and politics.

“It was a good match,” longtime friend and former Michigan attorney general Frank Kelley said of Dingell’s second marriage. “She was his moral compass. People in public life need a powerful spouse.”

While living modestly, despite their wealth largely tied to Debbie Dingell’s inheritance, the Dingells dined with presidents and went to movies with other Washington power couples, such as former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan and NBC newswoman Andrea Mitchell.

John Dingell was never one to name drop, even though his hunting buddies included former President Bill Clinton, Secretary of State James Baker and Sen. Alan Simpson, R-Wyoming.

Dingell did work with Republicans, joining GOP Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder to help push an expansion of the Medicaid health care program for low-income Michigan residents in 2013.

But he spent some of his final years in Congress lamenting the lack of cooperation and compromise that often brought the passage of legislation to a grinding halt.

In his 2018 book, Dingell lamented that the institution has become a “mean-spirited place … devoid of bipartisanship,” recalling bygone days when members worked to find common ground for the good of the country.

“We’re not recognizing the fights are among ourselves, rather than Americans defending this nation and its flag against foreign opponents. I think that’s the important thing to keep in mind — this is where the danger lies,” Dingell said in a December interview.

“This country should recognize that we should work together and pull together to accomplish our great ends, which is the welfare and well-being of all Americans.”

On Oct. 2, 2013, he took to the House floor to complain when the federal government partially shut down. The Republican-controlled House was demanding reforms in the Affordable Care Act from the Democratic-led Senate and Obama in return for approving a budget to fund the government.

“I’ve never seen such small-minded, miserable behavior in this House of Representatives and such disregard of our responsibilities to the people,” Dingell said.

59 years Congressional challenges

There were bumps in the road for Dingell. In November 2008, he lost the chairmanship of the House Energy and Commerce Committee in a tremendous Democratic power struggle during California Rep. Nancy Pelosi’s first tenure as House speaker.

Dingell, a longtime supporter of the auto industry, was ousted by Pelosi ally and environmentalist Rep. Henry Waxman, also of California. The panel has broad jurisdiction over the environment, energy, consumer protection, telecommunications, and health care programs.

“I was absolutely astounded. But that is part of life. A little man would whine. A big man won’t. I hope I fall on the right side of that dividing line,” Dingell told two reporters privately afterward.

“I have had a significant loss of clout. I will have to make up for it with hard work and with extra effort.”

Republican Rep. Fred Upton’s office was across the hall from Dingell’s, and he recalled the day that Dingell lost the chairmanship.

“The California cabal is pretty strong, and Pelosi was for Waxman,” said Upton, who went on to chair the panel when the GOP gained the House majority.

“I remember talking to him that day. He said, ‘Fred, that’s the way that it is.'”

Upton credited Dingell, his mentor, for working both sides of the aisle. “He taught me a lot as chairman. He’s been a valuable friend,” Upton said.

Dingell, given the title “chairman emeritus,” would rebind. He played key roles in stabilizing the auto industry during the Great Recession, gathering must-win votes to pass Democratic signature bills and pushing forward Obama’s languishing health care reform initiative.

Rep. Bart Stupak, a former Democratic congressman from Menominee, said Dingell went from being chairman of a committee to chairman of the House.

“Everyone still always calls him, ‘Mr. Chairman,’” Stupak said in an interview before his mentor’s death.

But Dingell’s legacy was defined mainly from when the chairman’s gavel was in his hand. A staffer in jest once put a framed picture of the Earth at the committee’s doorway to convey Dingell’s authority as chairman. The congressman never took it down.

‘Impressive foe.’

While his power didn’t wane, the decades of grueling work hours took their toll. Dingell wore a hearing aid and, after his second hip implant, often used crutches or a cane to help him get to votes and committee hearings.

At 82, he had a full knee replacement. He downplayed the potential seriousness of surgery at his age with characteristic humor: “My docs tell me the time is right to trade up, so I have my eye on a new, 2009 American-made model.”

In his later years in office, he kept up with the constant motion of Capitol Hill by using a cranberry-colored electric scooter with the nameplate, “The Dean.”

He tapped the latest technology to reach busy constituents, recording podcasts of his ideas for download, and maintaining a lively Twitter account that earned him the title “tweet king” by Politico’s Playbook.

“Many things have been said of me over the years, not all of them fit for polite company. I have been called ‘abrasive,’ ‘arrogant,’ ‘high-handed’ and by my friend, former President George W. Bush, ‘a pain in the ass,’ which I considered then, and still do, a high compliment,” Dingell wrote in his book.

“Like all 10 presidents I served before him, I did chafe his hind end on more than one occasion if I thought it was warranted.”

Even political adversaries marveled at how, despite his age, Dingell remained intellectually sharp and a political force.

“He was always an impressive foe, and I would have preferred to have him on my side,” said David Friedman, former research director of the Union of Concerned Scientists, who tangled with Dingell over higher fuel standards.

“You had to admire him when he would show up struggling with crutches. But then his brain would light up. No matter the battles with his health, he was fully engaged and ready for the fight.”

Friends saw qualities in Dingell of other larger-than-life politicians: Like President Teddy Roosevelt, he was a hunter who used his political power to protect the wilds.

Like Gerald Ford, who had been a Grand Rapids Republican congressman, Dingell had a life-long love affair with the U.S. House. He harbored no ambition to be a governor, senator or any other flashy political or business position.

Early days John Dingell, longest-serving member of US congress

Dingell was born July 8, 1926, in Colorado Springs to John Sr. and Grace. He was the eldest of three children.

Dingell would later say of his family, “I am the first of us who got through college. We were poor as Job’s turkey. Mom put paper in her shoes during the Depression.”

The Polish family’s name had been Dzieglewicz — meaning “blacksmith — but John Sr. modified it so he could campaign with the slogan, “Ring (in) with Dingell.”

John Sr. was elected to the 15th Congressional District as a Roosevelt “New Deal” Democrat in 1932. John Jr. served as a House page at age 12 and would grow up to be one of 24 congressional pages elected to Congress.

At age 15, he was a congressional page and on the House floor when President Franklin Roosevelt delivered his “day of infamy” speech after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, asking lawmakers to declare war against Japan.

In World War II, Dingell was drafted into the Army, rising to the rank of second lieutenant. He later credited his military service with teaching him discipline and respect, what he called “the keys to success in the United States.”

He got his law degree from Georgetown Law School and in 1952 married Helen Henebry, whom he met when he worked summers as a National Park Ranger in Colorado. They divorced in 1973.

Following his father’s death in 1955, the 29-year-old Dingell was elected to his House seat the same year. That’s also when McDonald’s opened its first restaurant and “The Ed Sullivan Show” won an Emmy for the best new show.

He inherited from his father a deep commitment to public service through politics.

“John Dingell got his vocation from his father — public service as the highest calling, just like the Kennedys,” Kelley said.

“He wanted to fulfill his father’s destiny. His love and respect for his father drove him. In some families, politics is like a religion. It certainly was for John Dingell.”

Early congressional years

In 1957, Dingell was appointed to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, which later became the Energy and Commerce Committee.

Drawing on his love of the outdoors, Dingell became a lead champion of laws to protect the environment. These included wetlands protection (1961), the National Wilderness Act (1964), the Water Quality Act (1965), a ban on ocean dumping (1971) and the Endangered Species Act (1973).

“Every day, Americans live in a world shaped by John Dingell,” said Larry Schweiger, former president of the National Wildlife Federation.

“He was a sportsman in the mold of Teddy Roosevelt who loved the outdoors and saw the need to protect them. He had the tenacity to get things done.”

Dingell was also a fierce gun-rights supporter and one-time member of the National Rifle Association’s board.

In the early 1970s, he was among the lawmakers who ensured the 1972 Consumer Product Safety Act explicitly exempted firearms from federal oversight under the newly created Consumer Product Safety Commission.

He later objected in 1975 when lawmakers tried to pass a measure to give the commission limited authority to require safety labeling on guns and ammunition and to set regulations to prevent the sale of defective firearms or ammunition.

Debbie Dingell introduced legislation in 2018 to give the commission that power, saying the federal government should have the authority to force defective guns off the market.

She broke the news to her husband in March that she was introducing legislation to “correct” what he did more than 40 years ago. His response at the time was, “Times have changed,” Debbie Dingell said.

‘Big John’ in the ’80s, ’90s

In 1981, John Dingell rose to chair the Energy and Commerce panel, as well as of its oversight and investigations subcommittee. He also remarried.

In his new role, the former Michigan prosecutor became known for his pit-bull investigatory style and was feared by administration officials and contractors.

He investigated wasteful spending of taxpayer dollars, the safety of the blood supply and insider trading. One Superfund administrator spent five months in jail after being convicted of lying to Dingell.

In a profile of Dingell, the New Yorker magazine wrote, “Congressional insiders liked to say he inspected the front seats after a hearing to see how much sweat the witnesses had left.”

Upton recalled that the first investigation Dingell spearheaded when Upton joined the committee in 1991 was that of Stanford University’s misuse of taxpayer money.

The panel caught Stanford charging taxpayers $184,000 for a 72-foot luxury yacht, and the defense contractor General Dynamics billing the federal government for boarding a dog named Fursten.

Dingell demanded so much accountability by federal agencies that the sole job of one woman at the Environmental Protection Agency was to respond to “Dingell-Grams.” She took to calling herself “Mrs. Dingell.”

Back as ‘Mr. Chairman’

After the Democrats regained control of Congress in 2006, Dingell regained the chairman’s gavel.

Dingell turned his focus to helping forge a workable increase in fuel economy standards (signed into law in 2007), banning lead in children’s toys and products (signed into law in 2008), and requiring insurers to cover mental illnesses the same as other illnesses (signed into law in 2008).

“I would hate to think of what Congress would have done to the auto industry but for John Dingell,” said David Cole, chairman emeritus of the Center for Automotive Research.

“John was a moderating force in the Democratic Party about the auto industry. He bridged the gap between those deciding public policy and those who had to deal with the reality of running a business,” Cole added.

In June 2013, Dingell overtook West Virginia Democrat Robert Byrd — who recorded 20,996 days of service in the House and Senate — as the longest-serving member of Congress.

In his last years, Dingell also threw himself into an ongoing effort to overhaul the nation’s food and drug laws, cracking down on contaminated food and drugs from China, and developing legislation to reduce greenhouse gases.

Even with Dingell’s long list of legislative accomplishments, former U.S. House historian Robert Remini contended that Dingell’s “my way or the highway” style left him short of reaching the heights of the nation’s greatest politicians, such as House Speaker Sam Rayburn.

“He was a powerful man, yes,” Remini said before his death in 2013, “but not among the greatest. That takes leadership that brings about compromise.”

Friend Kelley said Dingell would be happy to be remembered as “one of Michigan’s most outstanding public servants.”

Source the Detroit News.