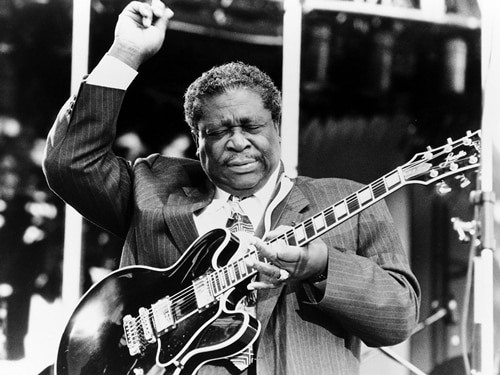

B.B. King the legend remember!

B.B. King, the larger-than-life guitarist and singer who helped popularize electric blues and brought it to audiences for more than six decades, died Thursday in Las Vegas. He was 89. King, who was diagnosed with diabetes nearly 30 years ago, was hospitalized last month due to dehydration. Last October, he was forced to cancel eight tour dates for dehydration and exhaustion. His attorney, Brent Bryson, confirmed his death to the Associated Press.

B.B. King, the larger-than-life guitarist and singer who helped popularize electric blues and brought it to audiences for more than six decades, died Thursday in Las Vegas. He was 89. King, who was diagnosed with diabetes nearly 30 years ago, was hospitalized last month due to dehydration. Last October, he was forced to cancel eight tour dates for dehydration and exhaustion. His attorney, Brent Bryson, confirmed his death to the Associated Press.

Into his late eighties, King toured the world year-round as the unrivaled ambassador of the blues. His indelible style – a throaty, throttling vocal howl paired with a ringing single-note vibrato sound played on his electric guitar named Lucille – defined the genre. He won 15 Grammy Awards and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987.

“He is without a doubt the most important artist the blues has ever produced,” Eric Clapton wrote in his 2008 biography, “and the most humble and genuine man you would ever wish to meet. In terms of scale or stature, I believe that if Robert Johnson was reincarnated, he is probably B.B. King.”

King didn’t do anything small; his excesses included food, women, (he claimed to have fathered 15 children by 15 different partners) and gambling (he moved to Las Vegas in 1975). His sound was also big: Speaking about “When Love Comes to Town,” U2’s 1988 duet with King, Bono recalled, “I gave it my absolute everything I had in that howl at the start of the song. And then B.B. King opened up his mouth and I felt like a girl. We had learned and absorbed, but the more we tried to be like B.B., the less convincing we were.”

He was born Riley B. King in Itta Bena, Mississippi, on September 16th, 1925. His young parents divorced when he was five and his mother died when he was nine, leaving him to be raised by his maternal grandmother. King dropped out of school in tenth grade (though he vigorously studied math and languages until late in his life) and earned a living picking cotton for a penny a pound and singing gospel songs on a local street corner, studying music under cousin Bukka White. He married at 17. “I guess I was looking for love, because I never had anybody I believed truly loved me,” he told Rolling Stone in 1998. It was the first of two failed marriages. “Since my early childhood, I have had a problem trying to open up. Please open me up. Look inside! ‘Cause I can’t. I don’t know how to.”

In 1948, King was living in Memphis working as a tractor driver when he landed a gig on Sonny Boy Williamson’s local radio show. That led to a job at a popular West Memphis juke joint playing six nights a week, earning $12 a night, In Memphis, he met artists like Louis Jordan and T-Bone Walker, where he heard electric guitar for the first time. “T-Bone was, to me, that sound of being in heaven,” he said.

King scored his first Number One hit in 1951 with “3 O’ Clock Blues.” Dozens more followed in the coming decades, including 1954’s “You Upset Me Baby,” 1960’s “Sweet Sixteen.” One night in 1949, King was performing at a dance in Twist, Arkansas, when two men started fighting over a woman named Lucille and set the club on fire by knocking over the kerosene stove. The place was evacuated, but King rushed back inside to retrieve his guitar, which he dubbed Lucille. Despite being married twice, King has said that Lucille was his true love, and he called every guitar he owned after that Lucille as well. “‘Lucille’ is real,” King once wrote. “When I play her, it’s almost like hearing words, and of course, naturally I hear cries. I’d be playing sometimes as I’d play, it seems like it almost has a conversation with me. It tells you something. It communicates with me.”

In the Sixties, the success of blues-influenced British bands helped broaden King’s appeal. He began to perform for white rock audiences with acts like the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton. Around this time, his sound started to change. When Rolling Stone included King among the 100 Greatest Guitarists, Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top said, “There was a turning point, around the time of [1965’s] Live at the Regal, when his sound took on a personality that is untampered with today – this roundish tone, where the front pickup is out of phase with the rear pickup. And B.B. still plays a Gibson amplifier that is long out of production. His sound comes from that combination. It’s just B.B.” Some of King’s greatest recordings are live albums, including Live in Japan and Live at Cook County Jail, which showcase his masterful delivery and playful, old school showmanship.

In the late Sixties, King moved to New York and started working with manager Sid Seidenberg, who helped curb his gambling habit and got King playing larger venues and festival dates. King started having hits again, including 1968’s “Paying the Cost to Be the Boss,” 1969’s cutting social commentary “Why I Sing the Blues” and “The Thrill Is Gone” (originally recorded in 1951 by Roy Hawkins), a spooky minor-key stomp with string overdubs that earned King a Grammy in 1970 and was named Number 185 on Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. King’s blues didn’t wallow; his best songs mixed humor with deep-rooted soul. “There’s always been a myth about the blues singer,” King once said. “There’s something about the blues singer that was always terrible one way or the other. And that was the myth that I heard from the beginning. [I’m] crazy about women. If there was no ladies, I wouldn’t wanna be on the planet. Ladies, friends and music – without those three, I wouldn’t wanna be here.”

In the late Sixties, King moved to New York and started working with manager Sid Seidenberg, who helped curb his gambling habit and got King playing larger venues and festival dates. King started having hits again, including 1968’s “Paying the Cost to Be the Boss,” 1969’s cutting social commentary “Why I Sing the Blues” and “The Thrill Is Gone” (originally recorded in 1951 by Roy Hawkins), a spooky minor-key stomp with string overdubs that earned King a Grammy in 1970 and was named Number 185 on Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. King’s blues didn’t wallow; his best songs mixed humor with deep-rooted soul. “There’s always been a myth about the blues singer,” King once said. “There’s something about the blues singer that was always terrible one way or the other. And that was the myth that I heard from the beginning. [I’m] crazy about women. If there was no ladies, I wouldn’t wanna be on the planet. Ladies, friends and music – without those three, I wouldn’t wanna be here.”

In the Seventies, King also recorded albums with longtime friend and onetime chauffeur Bobby Bland, 1974’s Together for the First Time…Live and 1976’s Together Again…Live, and Stevie Wonder co-wrote his 1973 song “To Know You Is to Love You.” In 1988, he recorded “When Love Comes To Town” for U2’s album Rattle and Hum. Bono later recalled an anecdote from the session: “When we were working, we were showing him the chords and he said,’ gentlemen. I don’t do chords. I do this [referencing King’s soloing style]. There’s a lesson in that. He is, as Keith Richards describes, a specialist.”

Said King, “Blues purists never cared for me. I don’t worry about it. I think if it this way: When I made ‘Three O’ Clock Blues’, they were not there. The people out there made the tune. And blues purists just wrote about it. The people is who I’m trying to satisfy.”

King’ style – marked by his signature ringing, vibrato notes – became a hallmark of blues playing, imitated by everyone from Clapton to Buddy Guy. “I always liked the steel guitar. I also love the guys that play the bottleneck,” King said. “But I could never do it; I never made it do what I want. So every time I would pick up the guitar, I ‘d shake my hand and trill it a bit. For some strange reason my ears would say to me that sounds similar to what those guys were doing. I can’t pick up the guitar now without doing it. So that’s how I got into making my sound. It was nothing pretty. Just trying to please myself. I heard that sound.”

“Very seldom does he talks about the way he play, man,” Buddy Guy told Rolling Stone last year. “He always wanna talk about young women. And I fuss at him sometimes, I say, ‘Man I wanna know what did you do here!'”

Blues legend B.B. King dies at age 89

In 1991, B.B. King’s Blues Club opened in Memphis. Soon, he’d have clubs throughout the country. He continued to enjoy commercial success late into his career. In 2000, Riding With the King, an album recorded with Eric Clapton, topped the Blues Albums chart and went double-platinum. A 1998 Rolling Stone feature by Gerri Hirshey estimated that King had played more than 15,000 concerts. He spent more than 65 years on the road, playing more than 300 shows a year until cutting back to around a 100 during the last decade. “We worked our asses off from ’63 to ’66, right through those three years, non-stop,” Keith Richards once said. “I believe we had two weeks off. That’s nothing, I mean I tell that to B.B. King and he’ll say, ‘I been doing it for years.'” King was also an entertainer off stage, regularly holding meet and greets, where he chatted with fans and “guitar kids,” as he called them, long after the house lights turned on. “At the Crossroads concerts, the first one I did, I was a nervous wreck,” Gary Clark Jr. told Rolling Stone last year. “It was a big day for me. I walked across the stage and B.B. kind of grabbed my hand, looked up at me, and just kind of nodded. That was one of those moments where I was like, ‘B.B. King is smiling at me. Everything is going to be all right. Yeah, I can go on with my life.”

King was also an avid reader and Internet enthusiast who once schooled a young reporter on how to transfer vinyl to MP3. “Gosh, I don’t know how I lived without it!” he once said of the computer.

“I’m slower,” he told Rolling Stone in 2013. “As you get older, your fingers sometimes swell. But I’ve missed 18 days in 65 years. Sometimes guys will just take off; I’ve never done that. If I’m booked to play, I go and play.”

He added, “The crowds treat me like my last name. When I go onstage people usually stand up, I never ask them to, but they do. They stand up and they don’t know how much I appreciate it.”

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=videoseries?list=PL9nqFX-3qd00ExAbzoTUL3tgbqpzxC2lD]

Reference: